|

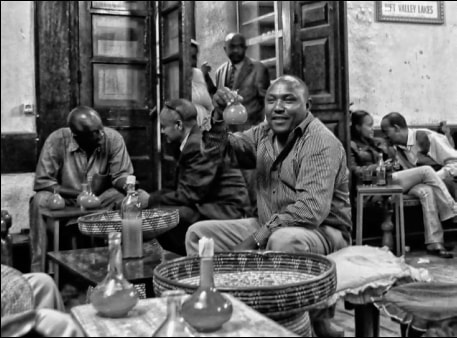

The variety of fermented drinks from Africa are many. There’s Bouza, Palm wines, Muratina and Uragua, Kaffir, Wanzuki and Gongo, Kofyar, Banana beer, Ikigage, and Tchoukouto, just to name a few. Each with their own cultural traditions. Each with their own variations. Let’s get started. Ethiopian Honey WineEthiopia is home to a fair number of drinks, such as Tej, Tella, Borde and Shamita. Tej is a fairly well known drink. And by well known, I mean you actually get results when you google ‘Tej wine’. Tej is a mead brewed with gesho (Rhamnus prenoides). According to Vogel and Gobezie (1981) it is prepared with one part honey with 2 - 5 parts water, covered, then left to ferment for 2 - 3 days. A portion (Im not sure how much) is boiled with the gesho root, then put back into the fermentation pot. Then its left to ferment till completion (5 to 20 days), then filtered. Tej HistoryThere is some folklore with Tej, once the reserved drink for Royalty, now considered the national drink of Ethiopia. Even in the Ethiopian episode of Parts Unknown, Anthony Bourdain heads to a local Tej Bet (a Tej bar) for a drink. The segment is short, and Bourdain only mentions that Tej is a fermented barley and honey drink. Not much, but at least it’s some tv coverage of the beverage. It has been argued before [Hayden et al., 2013] that honey was one of the only simple sugar sources available to prehistoric man, and thus Tej could be used as an example for potential Neolithic beverages. It stands to reason that Tej, or any other form of mead, was one of Man’s first alcoholic brews. If honey is exposed to some water, the simple sugars present will provide the energy for yeast to start fermentation. Whether or not archaeologists will be able to prove this is another story. Turning to the section regarding honey and Africa, Dr. McGovern in Uncorking the Past mentions that the Roman geographer Strabo [63 BC - 24 AD] noted that Tej was brewed by the nomadic peoples of the area and consumed exclusively by the ruler and his advisers. When this drink transitioned from the drink of royalty, to the drink of the commoner I do not know. According to McGovern, Tej is made by mixing five to six parts water with one part honey, allowing it to sit for a few weeks to ferment, resulting in a mead around 8 - 13% alcohol. McGovern doesn’t go into Tej any further, but instead diverges into a brief history of mead in the area. Something I should get back to. Given that McGovern is discussing the beginnings of Tej, it is entirely possible that Tej was a mead which evolved into something else in the future. Plus, given the cultural diversity of Africa, one village could make it entirely different from another. This section, although a fun read, is just another blip of information. Tej RecipeI think the reason I find this particular style so interesting is due to the lack of a defined recipe for Tej. One recipe, for instance, developed by Miriam Kresh, who had the help of two Ethiopians, says to use barley and wheat when brewing. In sum, she suggests using a mixture malted barley (or sprouted barley), cooked wheat grains, and semolina cakes as the starch sources to brew Tallah, an Ethiopian style beer. Then, once Tallah is finished fermenting, add honey to taste. So now according to this recipe, Tej is more of a braggot (barley and honey beer) than a mead. Like with all research, I seem to be generating more questions rather than solid answers.  But at least I found out about Tallah. From what I have read about African brewing practices, it seems common to mix different stages of grain fermentations to create one batch. More on that later. Another source claims that Tej is a simple mead with Gesho root as a flavoring (possibly preservative?). Harry Kloman’s Tej page discusses the evolution of the word Tej in the Amharic languages, highlighting the difficulties therein. He then goes on to list some literary sources, usually stemming from explorers of the area, who mention Tej in their travels. Either the result of human error or cultural variation, each account of Tej is slightly different, varying the ratios between honey and water, additives, and whether cereal grains were used. The most relevant quote stems from Robert Bourke in 1876 who says Tej is made in the following way: to one part of honey are added seven parts of water, and well mixed; then some leaves of a plant called "geshoo" are put into the mixture, to make it ferment; it is put outside in the shade and left for a day or two. A piece of cotton cloth is strained over the mouth of the large earthenware jar, or "gumbo," and through this the "tej" is poured; the servant tapping the cloth with his fingers to make the liquid run freely. It one wants to make it stronger, the first brew is used instead of the water; adding honey and geshoo leaves in the same way. This, along with the majority of quotes provided, shows that Tej is indeed a mead which uses Gesho as a bittering agent. Tej in Culture This also signifies the role Tej has played within a culture. The origins of state societies within Ethiopia (like the Aksumites) were fueled by political and economic contacts with Egypt, South Arabia, and the expansion of Rome. Since all three were major brewers of beer and wine, it would be interesting to see how Tej relates to other drinks at that time. Was Tej developed because the Kings and Queens of Ethiopia wanted to imitate what they saw in Egypt? Was Tej used as a trade good? When did Tej become a drink of the elite, when it can be so easily made at home? Were there taxes regulating the trade? Who knows... MicrofloraAt least there is some recent evidence with which fermentative organisms to use. In their paper published in 2005, Bahiru et al. studied the microflora from 200 samples of Tej at varying stages of development. Although there was significant variation, yeasts and lactic acid bacteria were most common, with S. cerevisiae and Lactobacillus being the dominant representatives. The authors suggest that the fermentative process of Tej probably proceeds as thus: Enterobacteriaceae initiate fermentation and then reduce pH levels until conditions are ideal for lactic acid bacteria and yeasts. However, the authors state that this area requires further research. What this study does show is the variety of organisms involved in fermentation (ten different yeast species, and at least four lactic acid bacteria). This just goes to show the level of experimentation that can be done with different microorganisms. Would be interesting to know if any form of control for fermentation was being done (such as a branch to collect yeast), but the authors don't mention anything. I imagine Tej tastes very sweet, but could have extreme variety given regional differences in resources. Given the rise of SABMiller, I just hope Tej and other indigenous beers don’t go extinct. ReferencesBahiru, Bekele, Tetemke Mehari, and Mogessie Ashenafi. "Yeast and lactic acid flora of tej, an indigenous Ethiopian honey wine: Variations within and between production units." Food microbiology 23.3 (2006): 277-282.

Hayden, B., Canuel, N., & Shanse, J. (2013). What was brewing in the Natufian? An archaeological assessment of brewing technology in the Epipaleolithic. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 20(1), 102-150. McGovern, P. E. (2009). Uncorking the past: the quest for wine, beer, and other alcoholic beverages. Univ of California Press. Vogel, A., Gobezie, A., 1983. Ethiopian ‘‘tej’’. In: Steinkraus, K.H. (Ed.), Handbook ofIndigenous Fermented Foods. Marcel Dekker, Inc, New York.

1 Comment

Mike Shiferaw

7/22/2024 11:09:22 pm

I don't know the exact process but growing up, I remember that sprouted wheat (for commercial tej, maize) used to be scattered to be dried with sunlight and my grandma used to tell me that goes into tej. When Tej is made of cereal, honey and gesho, they say it will definitely hit the spot. Especially, if it's maize

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Jordan RexBeer archaeologist Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed