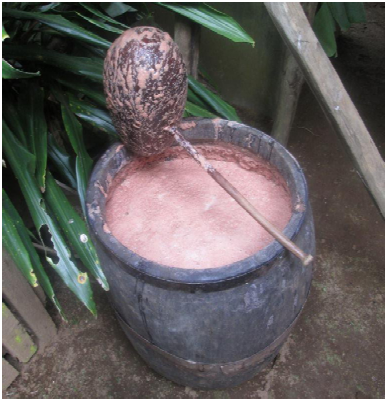

Banana beer from AfricaBeer is not confined to malted barley, hops and water as the reinheitsgebot would have you believe. Nor should it be limited to locally sourced barley and wheat and whatever the brewer found at the farmers market. If you define beer as any fermented beverage whose sugars are derived from cereals, it leaves room for much more experimentation. The easiest place for inspiration is our collective past. In Africa alone, it is said to have hundreds of beer styles. Plus, these indigenous alcoholic beverages account for 80% of consumption in rural Africa. However, these traditions are difficult to study given the negative influence of colonialism, no written record before European involvement, and the importation of foreign brands. Plus, the details that do exist remain unclear. Despite this, one tradition I find fascinating is the use of bananas in brewing. Mbege BeerEnter mbege, a banana beer brewed by the Chaga (Chagga, Wachaga) people in Tanzania. The Chaga tribe are within the Bantu-speaking group and the third largest ethnic group in Tanzania. Traditionally, they live on the southern and eastern slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro where the environment is highly suitable for agriculture. Although best known for Arabica coffee, the Chaga’s main crop is the banana which they use for cooking, brewing, and fruit. Mbege ProductionProduction is divided into three steps: Nyalu preparation, Mso preparation, followed by the mixing step. Nyalu Preparation Nyalu refers to fermented banana juice, which serves as the primary source for fermentative organisms. In the Chaga tribe, this is done by cooking a 1:1 ratio of ripened bananas to water. This mixture is then cooked over high temperature until the liquid turns red and no more clumps remain. This is then filtered and left to ferment (via open fermentation) for 9 - 12 days, depending on the season. Prior to fermentation, some brewers add powdered bark (called Msesewe) to the liquid. This bark, derived from the Rauvolfia caffra tree, provides a level of bitterness and aids in fermentation. In previous studies, it was seen that tannins from Mangrove tree bark serve as a protective agent against microbial infection, except for yeast. It is said that Nyalu produced with msesewe will finish fermenting within five days, due to the protective effects of the bark. I wouldn’t be surprised if it also served as an inoculant, given that some yeasts thrive on trees. The Chaga method of banana juice production seems to be one of the few that cook bananas to extract liquid. Other methods of banana juice production are to mash ripe bananas in a trough, removing the liquid through sieves of grass or banana leaves. For example, the Haya (a now disbanded kingdom in Tanzania) usually press bananas to extract liquid. It is unclear which method of juice extraction is best. It is entirely possible, though, that one method provides a different flavor than the other. Mso Preparation Once the Nyalu is close to finishing, the mso is prepared. Mso is simply an unfermented wort derived from malted finger millet. This is done by heating water and adding a small fraction of ground millet. Once it reaches temperature, roughly half of the liquid is removed and set aside. Then, the rest of the malted millet is added to the mix. This is then cooked for 25 minutes. The amylase present in millet is operative between 50 - 70 C (after which it denatures). To control temperature and thickness of the mash, the extracted liquid is added back to the mixture. If normal water was used, it would drop the temperature too low, thus stopping the mashing process. Plus, using the liquid Mso extract serves as a way to thin the mash in case it gets too thick. After the mash, the liquid is then moved to separate containers to cool. Mixing Once cood, nyalu and mso are mixed in a barrel. The resultant liquid is called togwa and left to ferment. Even after 6 hours, alcohol levels will rise to around 2.5%, but if left to ferment for two days, alcohol levels should reach roughly 4% abv. It is assumed that nyalu serves as the primary source for yeast, given that it is the only liquid left to ferment separately. The main fermentative organisms responsible were found to be Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Lactobacillus plantarum. Mbege beer recipeIn a previous study, the following amounts were reported:

Therefore, water to banana juice is 1:1, and for water to malt is roughly 1:3. If you were to attempt brewing mbege, then keeping these ratios should result in a solid recreation of the brew. Determining the amount of bananas required to produce adequate levels of juice have so far gone unreported. Further complicating this issue is the amount of banana cultivars present in Tanzania. In a previous study, a total of 18 varieties were reported, yet the total number is well over 100, with some names being synonyms and homonyms. Not much is known how nomenclature is derived, thus causing one of the biggest problems in classifying banana varieties. Plus in Tanzania, the farming of bananas is largely for local consumption, and so are bred to meet local tastes. Thus, choosing the right kind of banana to replicate this drink proves difficult. It is not as simple as just choosing cooking bananas, which are less sweet. Even more discouraging (but cool at the same time), there are banana cultivars specified for brewing. So locating the right type of banana may be impossible. Plus finger millet might be hard to come by, despite the advent of gluten-free beer. Yet I imagine it would be easier to acquire than the right kind of banana. Difficulties in studying mbegeKeep a dose of healthy skepticism when reviewing articles on mbege production. There is not much out there in regards to academic publishing. When there is, citing is somewhat scarce. For example, most just claim that the Chaga people are the founders of mbege, yet do not link it to other banana-based beverages. Given the diversity of tradition among tribes, mbege production might vary between groups within Tanzania, so observations of brewing might be tribe-specific. Plus, it is unclear whether the Chaga learned to make mbege on their own, or was taught to them by neighboring groups. European influences also have to be taken into account. In the early 1900s, British officials, scientists, missionaries, and settlers collectively condemned finger millet. They attempted to convince Chaga farmers of millet’s immorality, lack of market value, among others. At first, this advice was ignored, but by the 1980s, millet was only found sporadically. This, coupled with the fact that the written record for the Chaga people doesn’t begin until roughly 1850 skews historical accuracy. Still, this is a general overview of the practice and should be a decent representation of the tradition. ConclusionsI find one of the more inspirational takeaways is the banana juice as the source for inoculation, and finger millet as the source of simple sugars. With styles that have multiple sources of sugars, it would be interesting to experiment with a mbege-like fermentation profile (i.e. ferment one, use the other as sugars and vice versa). One such example would be the braggot, a barley-honey brew. Most braggot recipes I have come across state to mix both the barley wort and honey then ferment. It would be interesting to ferment the mead first, then add wort to see if that influences flavor. It is necessary to record methods of production of mbege and indigenous beverages on the whole, due to the anthropological role they play. IAB’s are accepted forms of payment for labor, are a source of income for women and provide an excellent source of nutrition. Thus, it is imperative to record their production techniques to preserve its place within humans material culture. ReferencesCarlson, R. G. 1990. Banana beer, Reciprocity, and Ancestor Propitiation among the Haya of Bukoba, Tanzania. Source Ethnol. 29: 297–311.

Kubo, R. 2014. Production of indigenous alcoholic beverages in a rural village of Tanzania. J. Inst. Brew. doi:10.1002/jib.127 Kubo, R., and M. Kilasara. 2016. Brewing Technique of Mbege, a Banana Beer Produced in Northeastern Tanzania. Beverages 2: 21. doi:10.3390/beverages2030021 Mwesigye, P. K., and T. O. Okurut. 1995. A Survey of the Production and Consumption of Traditional Alcoholic Beverages in Uganda. Process Biochem. doi:10.1016/0032-9592(94)00033-6 Platt, B. S. 2016. Some Traditional Alcoholic Beverages and their Importance in Indigenous African Communities. Quart. J. Stud. AZc. Nutr. Rev. Lancet Voeding Brit. med.J. i Arch. NeuroZ. Psychiat. Chicago Lancet 14: 257–287. doi:10.1079/PNS19550026 Shayo, N. B., S. A. M. Nnko, A. B. Gidamis ’, and V. M. Dillon2. 1998. Assessment of cyanogenic glucoside (cyanide) residues in Mbege: an opaque traditional Tanzanian beer. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 49: 333–338.

1 Comment

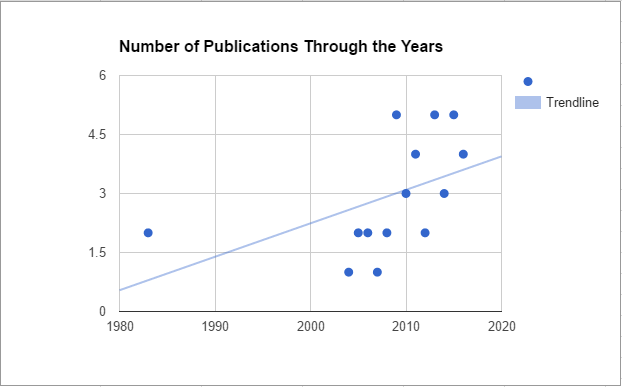

Brewing archaeology in Academic JournalsThe article The scholars who look at American History through Beer-Tinted Glasses claimed that an interest in beer history was on the rise. It certainly seems to be happening, what with the amount of talks, conferences, and blogs on the matter. This claim isn't necessarily unique either. Even in his 2006 paper, Alcohol: Anthropological/ Archaeological Perspectives, Dr. Michael Dietler states that a scholarly interest in the history of alcohol was on the rise. It is easy for me to assume this is true. I have payed more attention to the topic now than I did five years ago, which gives my assumptions bias. So to see whether research into alcohol within archaeology is increasing, I’ll be having a look through academic journals to track brewing archaeological articles. This time: Journal of Archaeological Science FindingsSo, it does appear that scholarly pursuits into beer history is indeed on the rise (albeit slowly). There have been only one or two publications up until 2009. After that, it seems the Journal of Archaeological Science publishes 4 - 5 articles about alcohol in archaeology. For whatever reason, 2009 does seem to be the year that kickstarted it all. However, I'll hold off any analysis until after I analyzed more journals. 2016

Pavelka, J. et al., 2016. Immunological detection of denatured proteins as a method for rapid identification of food residues on archaeological pottery. Journal of Archaeological Science, 73, pp.25–35. García Rivero, D., Jurado Núñez, J.M. & Taylor, R., 2016. Bell Beaker and the evolution of resource management strategies in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula. Journal of Archaeological Science, 72, pp.10–24. Garnier, N. & Valamoti, S.M., 2016. Prehistoric wine-making at Dikili Tash (Northern Greece): Integrating residue analysis and archaeobotany. Journal of Archaeological Science, 74, pp.195–206. Gismondi, A. et al., 2016. Grapevine carpological remains revealed the existence of a Neolithic domesticated Vitis vinifera L. specimen containing ancient DNA partially preserved in modern ecotypes. Journal of Archaeological Science, 69, pp.75–84. 2015 Barton, H., 2015. Cooking up recipes for ancient starch: assessing current methodologies and looking to the future. Journal of Archaeological Science, 56, pp.194–201. Lantos, I. et al., 2015. Maize consumption in pre-Hispanic south-central Andes: chemical and microscopic evidence from organic residues in archaeological pottery from western Tinogasta (Catamarca, Argentina). Journal of Archaeological Science, 55, pp.83–99. Nieuwenhuyse, O.P. et al., 2015. Tracing pottery use and the emergence of secondary product exploitation through lipid residue analysis at Late Neolithic Tell Sabi Abyad (Syria). Journal of Archaeological Science, 64, pp.54–66. Ting, C., 2015. Ancient and Historical Ceramics: Materials, Technology, Art, and Culinary Traditions. Journal of Archaeological Science, 59, pp.219–220. Vieugué, J., 2015. What were the recycled potsherds used for? Use-wear analysis of Early Neolithic ceramic tools from Bulgaria (6100–5600 cal. BC). Journal of Archaeological Science, 58, pp.89–102. 2014 Arobba, D. et al., 2014. Palaeobotanical, chemical and physical investigation of the content of an ancient wine amphora from the northern Tyrrhenian sea in Italy. Journal of Archaeological Science, 45, pp.226–233. Goldenberg, L., Neumann, R. & Weiner, S., 2014. Microscale distribution and concentration of preserved organic molecules with carbon–carbon double bonds in archaeological ceramics: relevance to the field of residue analysis. Journal of Archaeological Science, 42, pp.509–518. Washburn, D.K. et al., 2014. Chemical analysis of cacao residues in archaeological ceramics from North America: considerations of contamination, sample size and systematic controls. Journal of Archaeological Science, 50, pp.191–207. 2013 Gur-Arieh, S. et al., 2013. An ethnoarchaeological study of cooking installations in rural Uzbekistan: development of a new method for identification of fuel sources. Journal of Archaeological Science, 40(12), pp.4331–4347. Pecci, A., Cau Ontiveros, M.Á. & Garnier, N., 2013. Identifying wine and oil production: analysis of residues from Roman and Late Antique plastered vats. Journal of Archaeological Science, 40(12), pp.4491–4498. Pecci, A. et al., 2013. Identifying wine markers in ceramics and plasters using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Experimental and archaeological materials. Journal of Archaeological Science. Pető, Á. et al., 2013. Macro- and micro-archaeobotanical study of a vessel content from a Late Neolithic structured deposition from southeastern Hungary. Journal of Archaeological Science, 40(1), pp.58–71. Washburn, D.K., Washburn, W.N. & Shipkova, P.A., 2013. Cacao consumption during the 8th century at Alkali Ridge, southeastern Utah. Journal of Archaeological Science, 40(4), pp.2007–2013. 2012 Foley, B.P. et al., 2012. Aspects of ancient Greek trade re-evaluated with amphora DNA evidence. Journal of Archaeological Science, 39(2), pp.389–398. Reber, E.A. & Kerr, M.T., 2012. The persistence of caffeine in experimentally produced black drink residues. Journal of Archaeological Science, 39(7), pp.2312–2319. 2011 Barnard, H. et al., 2011. Chemical evidence for wine production around 4000 BCE in the Late Chalcolithic Near Eastern highlands. Journal of Archaeological Science, 38(5), pp.977–984. Gong, Y. et al., 2011. Investigation of ancient noodles, cakes, and millet at the Subeixi Site, Xinjiang, China. Journal of Archaeological Science, 38(2), pp.470–479. Milanesi, C. et al., 2011. Microscope observations and DNA analysis of wine residues from Roman amphorae found in Ukraine and from bottles of recent Tuscan wines. Journal of Archaeological Science. Washburn, D.K., Washburn, W.N. & Shipkova, P.A., 2011. The prehistoric drug trade: widespread consumption of cacao in Ancestral Pueblo and Hohokam communities in the American Southwest. Journal of Archaeological Science, 38(7), pp.1634–1640. 2010 Deforce, K., 2010. Pollen analysis of 15th century cesspits from the palace of the dukes of Burgundy in Bruges (Belgium): evidence for the use of honey from the western Mediterranean. Journal of Archaeological Science, 37(2), pp.337–342. Figueiral, I. et al., 2010. Archaeobotany, vine growing and wine producing in Roman Southern France: the site of Gasquinoy (Béziers, Hérault). Journal of Archaeological Science, 37(1), pp.139–149. Isaksson, S., Karlsson, C. & Eriksson, T., 2010. Ergosterol (5, 7, 22-ergostatrien-3β-ol) as a potential biomarker for alcohol fermentation in lipid residues from prehistoric pottery. Journal of Archaeological Science, 37(12), pp.3263–3268. 2009 Heaton, K. et al., 2009. Towards the application of desorption electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry (DESI-MS) to the analysis of ancient proteins from artefacts. Journal of Archaeological Science. Jiang, H.-E. et al., 2009. Evidence for early viticulture in China: proof of a grapevine (Vitis vinifera L., Vitaceae) in the Yanghai Tombs, Xinjiang. Journal of Archaeological Science, 36(7), pp.1458–1465. Namdar, D. et al., 2009. The contents of unusual cone-shaped vessels (cornets) from the Chalcolithic of the southern Levant. Journal of Archaeological Science, 36(3), pp.629–636. Romanus, K. et al., 2009. Wine and olive oil permeation in pitched and non-pitched ceramics: relation with results from archaeological amphorae from Sagalassos, Turkey. Journal of Archaeological Science. Seinfeld, D.M., von Nagy, C. & Pohl, M.D., 2009. Determining Olmec maize use through bulk stable carbon isotope analysis. Journal of Archaeological Science, 36(11), pp.2560–2565. 2008 Hein, A. et al., 2008. Koan amphorae from Halasarna – investigations in a Hellenistic amphora production centre. Journal of Archaeological Science, 35(4), pp.1049–1061. Stern, B. et al., 2008. New investigations into the Uluburun resin cargo. Journal of Archaeological Science, 35(8), pp.2188–2203. 2007 Barnard, H. et al., 2007. Mixed results of seven methods for organic residue analysis applied to one vessel with the residue of a known foodstuff. Journal of Archaeological Science, 34(1), pp.28–37. 2006 Guasch-Jané, M.R. et al., 2006. The origin of the ancient Egyptian drink Shedeh revealed using LC/MS/MS. Journal of Archaeological Science, 33(1), pp.98–101. Margaritis, E. & Jones, M., 2006. Beyond cereals: crop processing and Vitis vinifera L. Ethnography, experiment and charred grape remains from Hellenistic Greece. Journal of Archaeological Science, 33(6), pp.784–805. 2004 Bozarth, S.R. & Guderjan, T.H., 2004. Biosilicate analysis of residue in Maya dedicatory cache vessels from Blue Creek, Belize. Journal of Archaeological Science, 31(2), pp.205–215. Reber, E.A. & Evershed, R.P., 2004. Identification of maize in absorbed organic residues: a cautionary tale. Journal of Archaeological Science, 31(4), pp.399–410. 2003 Manen, J.-F. et al., 2003. Microsatellites from archaeological Vitis vinifera seeds allow a tentative assignment of the geographical origin of ancient cultivars. Journal of Archaeological Science, 30(6), pp.721–729. 1983 Knights, B.A. et al., 1983. Evidence concerning the roman military diet at Bearsden, Scotland, in the 2nd Century AD. Journal of Archaeological Science, 10(2), pp.139–152. Velde, B. & Courtois, L., 1983. Yellow garnets in roman amphorae—a possible tracer of ancient commerce. Journal of Archaeological Science, 10(6), pp.531–539. |

Jordan RexBeer archaeologist Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed