|

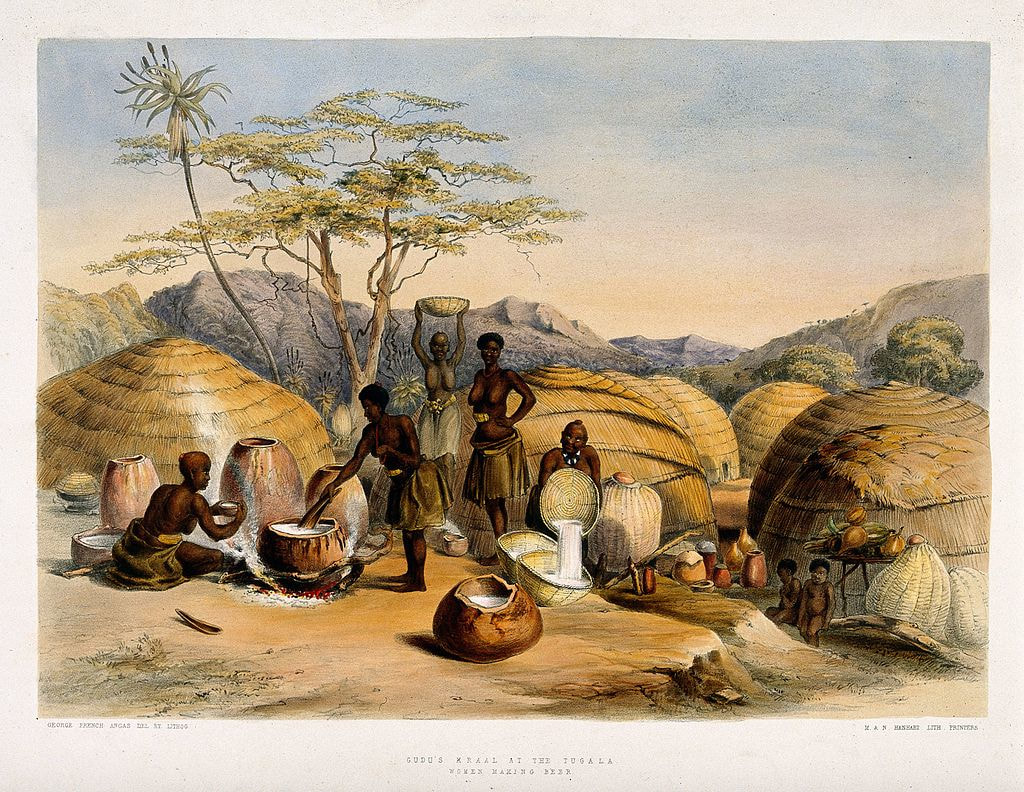

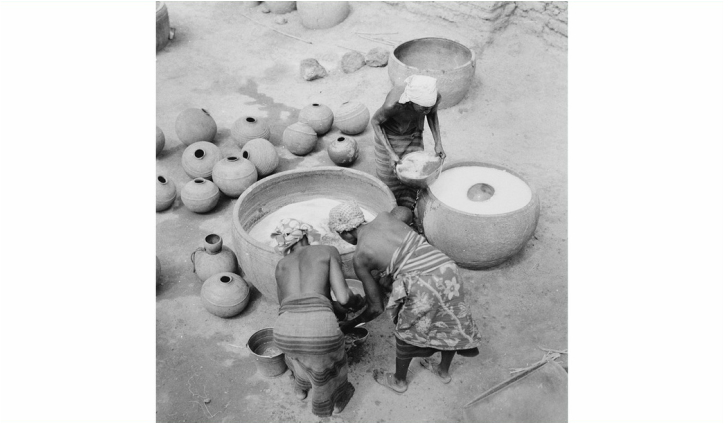

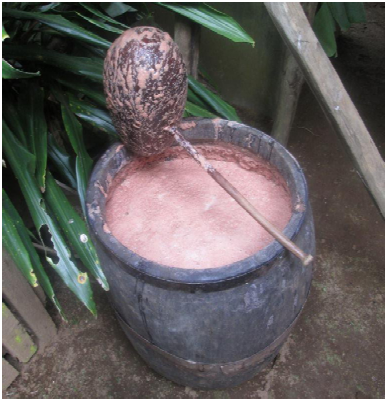

I am starting to realize that the Northeastern region of India is a major hub of rice beer brewing. Bear with me though, as it is somewhat challenging to meander through all the available information. Most sources refer to these drinks as wine, despite them actually being beer. Plus some tribes distill the fermented product while still calling it rice wine. So it is a bit confusing wading through the available information. Still, the preparation of alcoholic beverages from rice proves to be a fascinating topic, as it is prepared completely differently. Rice |

Jordan RexBeer archaeologist Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed